United Kingdom

The early 21st century is a novel time for social movements across much of Europe. The revolutionary left appears to have passed its sell-by-date, mobilization against the Iraq war is on the decline and summit-hopping and street parties that characterised the emergent ‘global justice movement’ at the end of the 1990s have lost popularity due to the violence that often accompanied them. Yet the time of large-scale marches and protest movements has not passed. Recent mobilizations, including the Make Poverty History March in Edinburgh, 2005, and the annual global climate campaign marches that pass through major cities, indicate that activists have not given up on protest (Rootes, 2003).

These observations raise important questions to which answers are often not known. Little is known about who attends such marches and why they do so. What are the characteristics of the protest participants? What concerns do they have about the issue on which they are campaigning? What is it about conventional politics that leads members of the public to attend protest marches? And do activists perceive their efforts to be a part of a global movement? Or is the global movement a mythical fragment of imagination?

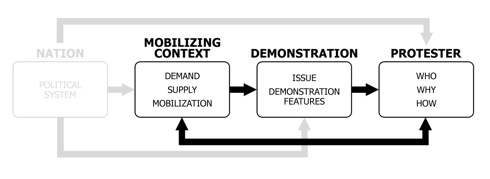

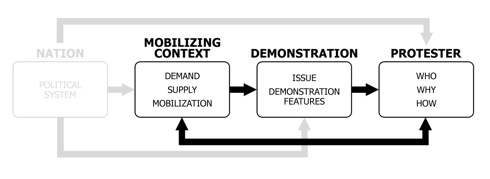

Figure 1. Interactions between mobilizing contexts, issues of demonstrations and protesters

The British team will concentrate on the issues people are demonstrating for and the way such issues impact on who participates in the demonstration for what reason. The team is also interested in how beliefs of the protestors feed back into the national mobilizing context (Figure 1). More specific the British team has two objectives. First, assessing protest behaviour as one of the means of political participation. How does protest participation relate to conventional political participation (Jenkins & Klandermans, 1995)? A number of questions in the core questionnaire concern political attitudes (political interest, left-right self placement, political cynicism), and conventional political participation such as voting behaviour. On the one hand, conventional and unconventional participation seem to be positively correlated (Barnes & Kaase, 1979). On the other hand, protest participation is conceived of as anti-politics, that is, inspired by people’s frustration about the political system.

Second, the British team will attempt to clarify the question of identification with transnational movements (della Porta, Kriesi, & Rucht, 1999; Della Porta & Tarrow, 2005; Smith & Fetner, 2007). For example, do protestors who take part in protest on issues of ‘Global Justice’ define themselves as part of this transnational social movement? Or do workers who protest against imminent changes in their pension system define that as protest against a national social policy issue or as protest against the transnational tendencies of neo-liberal economic reform? The core questionnaire contains the question of whether protestors perceive that their protest event is related to other protest events in the world, and if so to what extent they identify with these other protestors. In other words, do protestors feel part of or identify with a larger transnational social movement? An interesting question concerns the influence issues have on such definitions. To what extent do issues influence whether participants feel embedded in conventional politics and in transnational movements? Are some issues easier to embed in the conventional supply of politics than other? Similarly, are some issues easier to embed in transnational politics than other? Finally, if a protest is defined as being part of a transnational movement, what does that mean in terms of opponents?

These remain novel questions, to be explored by the UK team. As it is interested in these two matters it will analyse the data across countries looking into embeddedness in conventional political behaviour and in transnational movements. In doing so it explores how characteristics of participants feeds back into the characteristics of the mobilizing context. If participants feel that their participation is embedded in conventional politics and transnational movements, does that mean that they redefine the national mobilizing context?

Affiliated researchers:

- Chris Rootes | University of Kent

- Clare Saunders | University of Southampton

- Maria Grasso | University of Southampton

- Emily Rainsford | University of Southampton

- Cristiana Olcese | University of Southampton