Spain

Nowadays the dynamics of protest participation are more and more diverse. “Protest behavior is employed with greater frequency, by more diverse constituencies, and is used to represent a wider range of claims than ever before” (Meyer & Sidney, 1998: 4). This raises the question as to how all these different people where brought onto the streets. This question refers to mobilization. Mobilization is key to understand who protests for what reasons. However, our knowledge of the dynamics between the individual protester and mobilization techniques of movement organizations has remained limited. Indeed, “it would be interesting to know whether a specific strategy of consensus [or action] mobilization would activate a specific group of people” (Klandermans, 2003: 699).

The more so because there is an ongoing evolution from formal organizations to loosely coupled networks as mobilizing agencies (Duyvendak & Hurenkamp, 2004; Taylor, 2000). An important difference between these mobilizing agencies could be the employed communication channels. Classic mobilising organizations (e.g., unions) seem to rely on traditional information channels such as flyers, and organizational publications in targeting their members. In networks, however, the channels employed may be more diffuse, ranging from face-to-face contacts, internet, cell phones, to even general mass media. This broad variety in mobilization channels raises questions regarding effectiveness of employed channels. Are organizational publications, for example, more effective among workers and the Internet among students? Or are different information channels more effective in different stages of mobilization (i.e. consensus or action mobilization)? These are all important, yet largely unanswered questions. Understanding whether specific mobilization channels activate specific groups of people is key to understand who protests for what reasons.

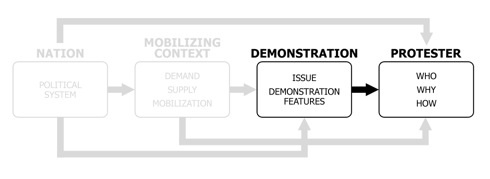

By contrasting organizational with informal network mobilization and their employed mobilization channels the Spanish Individual Project will make headway to understanding how people get mobilised and how that affects the socio-demographic characteristics of the protesters and their motivations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Research interest Spain

The Spanish team will focus on two questions:

- How people are mobilised and how that relates to the socio-demographic characteristics of the protest participants and their participation motives?

- How (in)effective are different mobilization channels among individuals who differ in terms of socio-demographic characteristics (who) and motivational dynamics (why)?

To answer the first question the Spanish individual project will fully correspond with the general project. That is, 8-12 demonstrations will be surveyed making use of two-staged protest surveys and diverse national socio-political and mobilizing context data, all gathered using the standardized measures and methods described in the general proposal (see Annex 2 for further details on the methods and measures of the general project).

To answer the second question regarding effectiveness of mobilization channels this project seeks to examine in more detail which mobilization channels are effective and which are not. Hence, in the general project, protesters are “caught in the act of protesting” which by definition implies that the employed mobilization channels were effective. Obviously, this method does not provide data on which mobilization channels are ineffective for whom. The protest surveys of the general project will be useful to get insight in how different mobilization channels spur motivation to participate in demonstrations with different issues. But, despite the comparative design, it remains difficult to arrive at robust conclusions about the causal link between mobilization channels and issues on the one hand and motivation on the other hand. Therefore the Spanish team plans to conduct a laboratory study in which the mobilization channels within different single-issue mobilization efforts will be manipulated to assess whether they appeal to different individuals, with different motives during different moments in the mobilization (see Research Design and methods section for further details).

Mobilization

Effective mobilization brings demand and supply of protest together (Klandermans, 2004). Social movements shape public views of reality by defining a problem and thus helping to make sense of often complex social and political reality. Besides this so-called consensus mobilization, social movements gear up for action mobilization, a process in which they aim to activate people to participate in the actions movements are staging (Klandermans, 1984). Klandermans and his collaborators broke action mobilization further down into four separate steps (Klandermans & Oegema, 1987). Each step brings the supply and demand of protest closer together until an individual eventually takes the final step to participate in protest.

The first step accounts for the results of consensus mobilization. It distinguishes the general public into those who sympathize with the issue and those who do not. The second step divides the sympathizers into those who have been target of action mobilization attempts and those who have not. The third step divides the sympathizers who have been targeted into those who are motivated to participate in the specific demonstration and those who are not. Finally, the fourth step differentiates the people who are motivated into those who end up participating and those who do not. With each step individuals drop out. The better the fit between demand and supply, the smaller the number of drop-outs. However, it is not known whether this fit is influenced by the employed mobilization channel (f.i. Internet, face-to-face, posters, newspapers etc.) and the issue at stake (f.i. conflicts on principles or conflicts on material interests). This project aims to fill that void.

Affiliated researchers:

- Jose-Manuel Sabucedo | University of Santiago de Compostela

- Eva Anduiza | Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona

- Camilo Cristancho | Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona

- Cristina Gomez | University of Santiago de Compostela

- Mauro Rodriguez | University of Santiago de Compostela